Not Really

By Lily

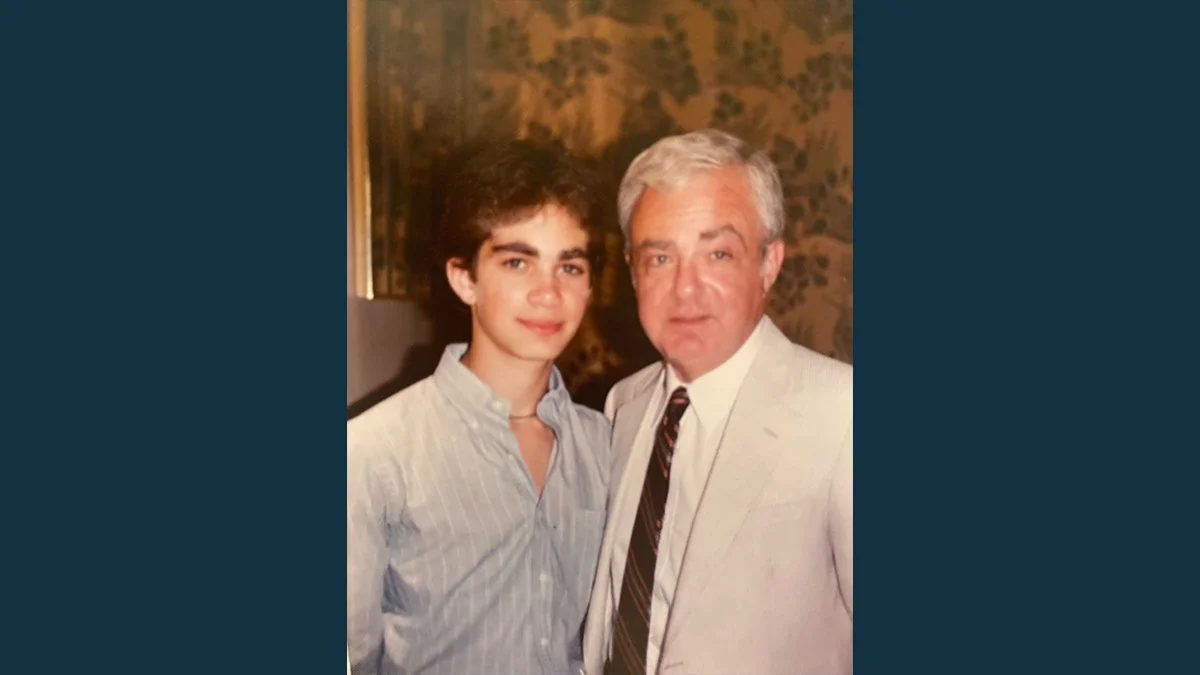

"What do we hold and what do we not? I went into the interview with my father holding a textbook description, a perfect prescription for what to ask, what to say, what to hear.

I wanted to ask, what do you hold? He told me what he didn't"

Lily: We've got a whole Fiddler on the Roof thing going on.

Jeff: Totally.

Lily: Tradition.

Jeff: I can sing, if that’s part of this…?

Lily: Well, I don't know if we need that.

Jeff: Okay.

Lily: What do we hold, and what do we not? I went into the interview with my father holding a textbook description, a perfect prescription, for what to ask, what to say, what to hear.

I wanted to ask, what do you hold? He told me what he didn't.

But, no definitive yes or no came to be—my father only kept some of his German ancestry.

Why did he take homemaking and cold cuts from Margaret, my grandmother with a thick accent, and English as her second language?

"Who gets to claim refugee?" He asked. Or rather, he told me that they had asked.

If you left before the worst, is what you experienced still worthy?

My grandparents departed in 1939 with their children, their car, their lives. All they lost was Germany, friends, and a home.

My father reentered his should-be homeland deaf to the language, blind to the nuances. He spoke to "real" Germans, who tried not to claim the sins of their ancestors.

They chose not to hold their past. My father didn't choose not to hold Germany. What do I hold?

Lily: Okay. So, tell me about our family on your dad's side. Where were they from, your dad, your grandparents?

Jeff: My father was born Rolf Hessekiel, R-O-L-F, in 1929, in Cologne, Germany. His parents, named Martin and Margaret Hessekiel, they owned a clothing store in Cologne and were kind of upper-middle class people there, although there was always a very strong strain of antisemitism in Germany and Central Europe in general.

Lily: Yeah. Right. This is the twenties, thirties, then?

Jeff: Well, it’s—he was born in 1929. So, yeah, this is the early twentieth century.

Lily: And they left.

Jeff: Right. So then, in the thirties, Adolf Hitler came to power and the Nazi party grew in Germany. And then in 1938, my Opa—opa being German for grandfather—and Oma decided that they could no longer stay there, it would be best for them to leave. And so they drove across the Swiss border in a car and were searched, and, somehow they escaped and they came to New York and they settled in Forest Hills, New York, and my father and his older brother named Heinz, or Harry, grew up going to school in Queens, New York.

Lily: What was it like for you growing up with a German father? I mean, he was what, thirty- nine, forty when you were born? And you, you don't know German. Did you ever want to be taught it?

Jeff: So, as I grew up, I was never particularly interested in learning German. I was born in 1969 and there was, there was still a strong strain… of anti-German feeling.

Lily: Right, post–World War II.

Jeff: Yeah. I mean, it's... when I grew up, it didn't feel like anywhere close to World War II, but as compared to now, it probably feels like, well, that wasn't that long after World War II.

Lily: Yeah, yeah.

Jeff: My German grandparents, my Oma and Opa, were just twenty-five minutes away, and we would see them frequently. They were intensely German people. They spoke with heavy German accents and I would eat lots of German cold cuts and they made beautiful German meals and lots of recipes, and also a very strong sense of a… pride of self and an elegance and they had a lovely home.

You can quickly sense when you talk to people who are German, who are of my generation, you get a sense perhaps of what their parents might have done during the war and, kind of a question as to whether or not there is an ancestral guilt, right? As to whether or not their parents were Nazis or, you know? And so, imagine a whole society that is laden with that self-doubt and guilt, you know, and the whole German people has suffered with that for many years.

So, my Oma and Opa were not actually in the Holocaust. They were not in the Shoah. They left as refugees really before they could be formally called refugees, although they certainly were, they were fleeing from political persecution in Germany, but, that's always been an interesting tension because… as compared to everything that happened after that, they were so fortunate that my father… it was always a strange feeling, like they didn't really feel the right to claim “survivors,” although they certainly fled for their lives with an idea of what was going to happen. They also, by the way, for the rest of their lives, after the war, they received reparation payments from the German government.

Lily: Oh, I didn't know that.

Jeff: Um, and so, until they died, my grandparents received a monthly check from Germany.

Lily: Wow.

Jeff: Yeah.

Lily: Yeah, I didn't know that.

Lily: I never met my Opa; he died before I was born. I've never been to Germany. I don't speak the language. I am now two generations removed from "not actually in the Holocaust." And yet, I feel a connection to Germany. From the place my family left.

That's undeniably my history. I think that in a small way, I get to hold it, too.